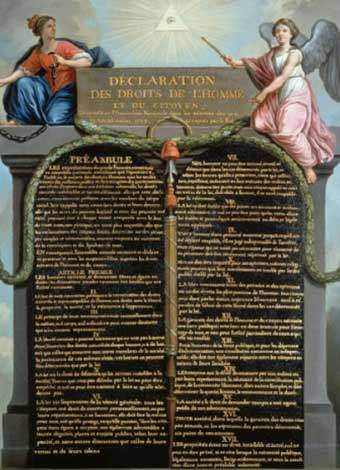

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was a pivotal document of the French Revolution and indeed, of modern democratic Europe. It was drafted in mid-1789 by members of the National Assembly, who crystallised Enlightenment positions on freedom, natural rights and human equality into a single document. The Declaration became a foundation stone of the revolution, though its ideals were seldom met and its principles were often transgressed.

Contents hideIn July 1789, the National Constituent Assembly began deliberating how to guarantee and protect individual rights in the new nation. One solution was to enact a document that codified [outlined in law] and explicitly protected these rights. Rights-based documents were already a feature of British law and at the time, the newly created United States of America was negotiating a bill of rights for its own constitution.

The National Assembly formed a committee to draft a bill of rights and, on August 26th 1789, passed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. This declaration became a cornerstone document of the French Revolution – and according to some historians, its greatest legacy.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen would serve as a preamble to all three revolutionary constitutions and a cornerstone document for political clubs and movements. It also set goals and standards for subsequent national governments – though these standards would be ignored and trampled during the radical phase of the revolution.

The main sponsor of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. A veteran of the American Revolution and a student of the philosophes, Lafayette embraced Enlightenment doctrines of constitutionalism, popular sovereignty and natural rights.

On July 11th, three days before the attack on the Bastille, Lafayette delivered an address to the Assembly, maintaining the need for a constitutional document that guaranteed the rights of individuals.

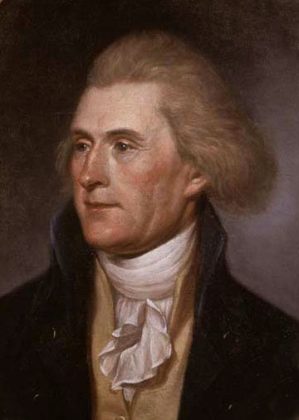

Lafayette went as far as tabling his own draft declaration of rights, prepared in consultation with Thomas Jefferson. A prominent writer and political leader, Jefferson authored some of the American Revolution’s most significant documents, including the Virginia Declaration of Rights and the United States Declaration of Independence (both 1776).

Despite Lafayette’s enthusiasm, there was considerable division in the Assembly about whether a declaration of rights was actually needed. Many of the points of difference that emerged continue in debates over rights-based laws today.

Most conservative and Monarchien (constitutional monarchist) deputies rejected the idea. They accepted that the royal government needed reform and limitations on its power – but they considered a bill of rights an unnecessary step. The Assembly’s more radical deputies thought otherwise. The new government, they argued, must have explicit constitutional limitations on its power, particularly where this power could infringe on individual liberties.

Other deputies had structural, procedural and legal concerns. What form should a declaration of rights take? Should it be part of the constitution? Should it exist as separate legislation? Should it be a broad philosophical statement or a legally binding set of points?

The debate continued through July and into the first days of August. On August 4th, the deputies reached a consensus about drafting a declaration of rights. Responsibility for this was given to the Assembly’s constitutional committee. This committee contained around 40 deputies, including Honore Mirabeau, Emmanuel Sieyès, Charles Talleyrand and Isaac Le Chapelier.

For six days the committee thrashed out a declaration of rights. They studied similar documents from Britain and America and received numerous submissions and drafts from interested locals.

The committee eventually emerged with a draft declaration of rights, containing a preamble and 24 articles. On August 26th, they whittled this back to 17 articles. The committee then voted to suspend deliberations and accept the draft as it stood, intending to review it after the finalisation of a constitution. Thus was born the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (in French, Déclaration des droits de l’homme et du citoyen).

The Declaration was a crystallisation of Enlightenment ideals. According to historian Lynn Hunt, it was “stunning in its sweep and simplicity”. It encapsulated the natural and civil rights espoused by writers like John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Jefferson, and entrenched them in French law.

It was a short document, containing only a preamble and 17 brief articles. These articles provided protection for numerous individual rights: liberty, property, freedom of speech and the press, freedom of religion and equal treatment before the law. The Declaration guaranteed property rights and asserted that taxation should be paid by all, in proportion to their means. It also asserted the concept of popular sovereignty: the idea that law and government existed to serve the public will, not to suppress it.

All of this was articulated in language that was clear, brief and unambiguous. The Declaration was also universal in its tone – its rights and ideas applied to all people, not just the citizens of France.

The Declaration was endorsed by the National Constituent Assembly and delivered to Louis XVI for endorsement. As Eric Hobsbawm puts it, the king “resisted with his usual stupidity” and refused to sign. He continued to refuse his assent until October 5th, when he signed the Declaration to placate angry crowds at Versailles.

Passed into law, the Declaration became a cornerstone of the revolution. The National Constitution Assembly adopted the Declaration as a preamble to the Constitution of 1791. An amended version of the Declaration also formed the basis of the Constitution of Year I, drafted by the Montagnards.

It also served as a beacon for revolutionary groups, both moderate and radical. The political clubs and cercles considered the document sacrosanct. The formal name of the Cordeliers club was the Société des Amis des droits de l’homme et du citoyen (‘Society of Friends of the Rights of Man and Citizen’) and a copy of the Declaration was pinned to the club’s wall beneath a pair of crossed daggers. The Jacobin rulebook required members to show loyalty to the Declaration and uphold its values at all times.

While the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was held up as sacred and inviolable, there was debate and disagreement about who these rights applied to.

Like the great documents of the American Revolution, the Declaration said nothing about the rights of women, nor did it extend any rights to the slaves and indentured servants in the colonies. This selectivity rankled with the most radical democrats. In October 1789, Robespierre used the Declaration to suggest that Jews – a marginalised group excluded from voting and political office, even during the revolution – were entitled to equality and civil rights.

Despite these gaps and shortcomings, the Declaration remains one of history’s foremost expressions of human rights. It served as a death warrant for the absolutist monarchy, an articulation of Enlightenment values, and a model for future societies seeking freedom and self-government.

“The August Decrees and Declaration of the Rights of Man represented the end of the absolutist, seigneurial and corporate structure of eighteenth-century France. They were also a proclamation of the principles of a new golden age. The Declaration, in particular, was an extraordinary document… Universal in its language and in its optimism, the Declaration was ambiguous on whether the propertyless, slaves and women would have political as well as legal equality, and silent on how the means to exercise one’s talents could be secured by those without education or property.”

Peter McPhee, historian

1. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was, as its name suggests, an articulation of individual rights. It was drafted in mid-1789, passed on August 26th and signed by the king in October.

2. The idea for a declaration of rights came from the Marquis de Lafayette, who provided his own draft, prepared in collaboration with American philosopher Thomas Jefferson.

3. The final Declaration was drafted by a committee of the National Constituent Assembly. It contained a preamble and 17 individual articles, guaranteeing and protecting specific rights.

4. The Declaration became a cornerstone document of the revolution. It served as a preamble to national constitutions and an inspiration to various political clubs and societies.

5. Like documents from the American Revolution, the Declaration did not specifically guarantee the rights of women, slaves or racial minorities, a fact highlighted by some political radicals.